We are pleased to share our longform piece detailing our findings about this historic trophy—won by a trailblazing French horse in the 1865 inaugural running of a race that continues to be contested annually at ParisLongchamp. Our research has been utilized to correct the erroneous information and is now referenced by the Walters Art Museum for this artwork.

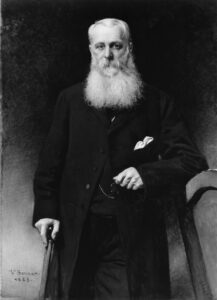

Sixteen racing trophies headlined the February 1884 estate auction of the late Count Frédéric de Lagrange, these “16 Prix De Courses” won for victories in France, England and Germany by Lagrange’s stable superstars including Monarque, his sons Gladiateur and Trocadéro, and filly Fille de l’Air. Hosted at the historic auction sales house Hôtel Drouot in Paris, the five-day sale was “only of interest to the turf,” it was overheard—“Portraits of Gladiateurs here, broken Gladiateur bits there; Gladiateur bridles, cufflinks with Gladiateur irons!”—though thousands of objects in addition to the trophies and sports memorabilia were offered from Lagrange’s Paris apartment and his Normandy estate Château de Dangu, the home of his Thoroughbred breeding farm, Haras de Dangu.

Lagrange could not have imagined the fate of his possessions, but one of the trophies, a silver lion sculpture by the French animalier Antoine-Louis Barye (1795*—1875) that sold for 6,905 francs, did not fall into obscurity. Today, “Walking Lion” (“Lion qui marche”) is on view to the public for the first time in a decade at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland.

Yet this French racing prize from 1865 has endured a mistaken identity for more than a century. Barye and Lagrange, the two men most closely connected to this piece who could confirm its details were both deceased, and once it changed hands at the auction, it was erroneously attributed to the wrong race by art historians—later creating confusion about the trophy’s rightful race as well as its winner.

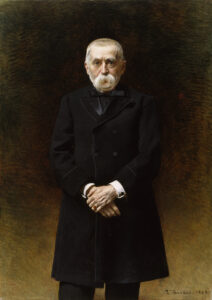

“Walking Lion” arrived in the U.S. in 1885 through its purchase by William T. Walters, the museum’s patriarchal namesake and preeminent American collector of Barye’s work. A secessionist who made his fortune in the liquor and transportation industries, Walters began acquiring the sculptor’s art while living abroad in Paris during the Civil War.

While some of Lagrange’s other trophies were obtained by members of the French Jockey Club, Walters could also have missed the opportunity to acquire “Walking Lion.” His art agent in Paris, George Lucas, wrote him immediately following the auction about the sculpture—then in the possession of dealer J. Montaignac with a selling price of 12,000 francs—but it was not purchased until nearly a year later in January 1885 for 10,500 francs. Incidentally, Lucas had contacted another client about the trophy just weeks before Walters’ purchase, writing in early January about “Montaignac’s Silver Barye Lion” to Samuel Avery, the New York gallery owner and founding trustee of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Henry Walters, who continued his father’s efforts in assembling the vast collection of artwork that includes hundreds of Barye’s bronzes and drawings, gifted the family’s gallery and collection to the City of Baltimore upon his death in 1931, the trophy being just one of 22,000 foundational objects contributed to the eponymous museum.

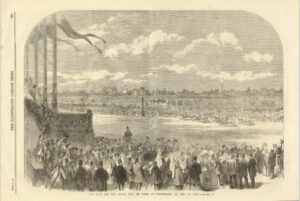

But why the mystery surrounding the trophy’s rightful race and recipient? The Lagrange sale catalogue did not reference the race’s name, listing the piece as “Lion marchant, de Barye,” won by Fille de l’Air in Paris in 1865; the inscription incised in gold letters upon the sculpture’s black marble plinth revealed the date of the race with the winning filly’s name: “PARIS 30 AVRIL 1865” and “FILLE DE L’AIR.” In the years following, several publications repeated the same misinformation: a Harper’s New Monthly Magazine article and three Barye biographies incorrectly associated “Walking Lion” with the 1865 Grand Prix de Paris, then run at 1m7f at the Longchamp track. Inaugurated in 1863, this race was held at the new l’hippodrome established in 1857 on the Longchamp plain bordering the Seine in the Bois de Boulogne, the Paris race meetings previously being run at the unsuitable location of the Champ de Mars military training grounds. As France’s premier race, the Grand Prix de Paris was scheduled in June two weeks after the Derby Stakes at Epsom and the Prix du Jockey Club (French Derby) at Chantilly, enabling the top three-year-olds to compete in this international contest that awarded an unprecedented French purse of 100,000 francs, as well as an art object presented by the Emperor of the French, Napoleon III.

Theodore Child’s “Antoine Louis Barye” piece for Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in September 1885 contained the first inaccurate race references. “The Grand Prix of 1865, which fell to the Count de la Grange’s (sic) ‘Fille de l’Air,’ was a commission that Barye greatly enjoyed,” stated an article footnote by William Laffan, a Harper’s editor and art consultant to Walters. Accompanying the article was an engraving of the trophy, “The Grand Prize of 1865—Executed in Silver by Barye, and Now in the Walters Collection.” This illustration was prepared for the magazine from the sculpture Walters had acquired just months before, the piece then displayed in the dedicated “Barye Room” of the artist’s works in Walters’ home gallery. The dimensions of this prized trophy are 19 ½ x 26 ¾ x 8 ¾ inches, according to the Walters Art Museum.

In 1889, two newly published biographies discussed the trophy’s race. Arsène Alexandre’s “Les Artistes Célèbres, A.L. Barye,” stated that the sculptor cast his “Lion qui marche” in silver for the occasion of the “grand prix of 1865,” won by Count de Lagrange’s Fille de l’Air. The Barye Monument Association for which Walters was president published the first English-language biography of Barye later that year in November, written by New York Times Art Critic Charles De Kay.

“When a piece of silver was needed for the Grand Prix at the Longchamps (sic) races,” wrote De Kay, “Barye was asked to put in solid silver his Walking Lion, that august beast which shows in its gait as well as its face an anger colossal, yet as cold as befits a sovereign without ruth accustomed to destroy whatever comes in his path.”

Roger Ballu also confused details in his 1890 biography, “L’Oeuvre De Barye.” Translated from French, he wrote, “Do you remember what happened on April 30, 1865? It was a Sunday; the crowd was crammed into a special spot in the Bois de Boulogne….All of elegant Paris was in celebration: the day of the races, the grand prize of a hundred thousand francs, had come….Enthusiastic cheers from the stands, from the weighing room, and the multitude crowded at the racecourse seemed to be in the grip of a patriotic delirium. The English horse was beaten. The mare Fille de l’Air, owned by Monsieur de Lagrange, whose jockey wore a tricolor coat, had won the race.”

The emperor awarded the winning owner a trophy, Ballu continued—“That year, the art object was a silver lion worth ten thousand francs. It was signed Barye. It was the famous Lion qui marche.”

Despite Ballu’s accurate description of the victory of the French-bred, four-year-old filly Fille de l’Air [by Faugh-a-Ballagh, out of unraced Pauline] in a two-horse race over “the English horse” on April 30, 1865, this race that he described was not the Grand Prix de Paris. The 1865 Grand Prix de Paris for three-year-olds was held on June 11, with its remarkable purse of 100,000 francs and a trophy, another art object but not “Walking Lion,” that was presented by Napoleon III to Count de Lagrange, who on this occasion was the owner of the winning colt Gladiateur, stablemate of Fille de l’Air!

It would have been easy for these writers to muddle details about a race that occurred 20 years prior; the mistake could have been due to the Grand Prix de Paris’ award of another art object to Count de Lagrange the same year and this international race being the most prominent French contest. The misinformation could have originated from the trophy’s dealer Montaignac, who had it in his possession for more than a year until its sale to Walters, or from Barye’s widow, who corresponded with Walters about “Walking Lion” following its purchase. A common denominator among all parties was Walters’ agent Lucas, the purchaser of “Walking Lion” whose diary recorded his interactions among the following: Madame Barye, whom he frequently visited to buy her late husband’s artwork, including a meeting the day after the trophy purchase; Theodore Child, his close friend and whose Harper’s article he read before it was published; Arsène Alexandre, who visited him “about Barye” in January 1889, the year of his book’s publication; and Roger Ballu, who copied Lucas’ Barye correspondence and used photographs of his Barye bronzes for the biography, which Lucas had the opportunity to read in late 1889 in advance of its publication.

Indeed, regardless of its source, the erroneous attribution of “Walking Lion” to the Grand Prix de Paris ultimately created confusion once the discrepancy was discovered, since that race’s 1865 winner, Gladiateur, is not listed on the trophy. According to the museum’s original description of the piece, it was reasoned that the inscription on the plinth must have been created years after the race and was mistakenly credited to Fille de l’Air. Yet “Walking Lion” does belong to this celebrated filly, and though her name, Fille de l’Air, the “Girl of the Air” sounds genteel—a horse gliding on air—she too possessed the mettle of a warrior like her stablemate.

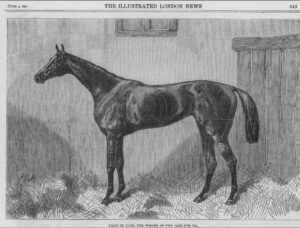

In 1863, Count de Lagrange’s French filly had already dominated England as a two-year-old, two years before her aptly named stablemate Gladiateur conquered the racing world by sweeping the English Triple Crown races. In her juvenile year while in training in England under Tom Jennings, Fille de l’Air won five of nine races there while placing in the remaining four, with victories at Epsom, Goodwood, Newmarket and Brighton.

“These performances caused such a sensation that Fille de l’Air was seen as a filly with a great future, and in the enthusiasm of the moment, people did not hesitate to compare her to the famous Crucifix,” wrote Henry Lee, translated from his 1910 book, “Historique Des Courses De Cheveaux, De L’Antiquité À Ce Jour,” in which he spoke of the undefeated English filly who won nine races at age two, followed by triumphs in both the 2,000 and 1,000 Guineas at Newmarket and the Epsom Oaks in 1840.

Historian Robert Black deemed Gladiateur as the “hero of 1865,” and Fille de l’Air was likewise deservedly called the “heroine of 1864,” who globe-trotted across three countries to compete in her three-year-old year. Despite finishing unplaced in the 2,000 Guineas and third in the Poule d’Essai (French Guineas, then open to colts and fillies), she rebounded with an easy win in the Prix de Diane (French Oaks) and “as if her health had been improved by a taste of her native air, she returned and won the Epsom Oaks, causing a disgraceful riot,” wrote Black in his 1886 book, “Horse-Racing in France: A History.”

“There was ‘scandal against Queen Elizabeth;’ it was murmured that Fille de l’Air was ‘very elder than her looks,’” wrote Black. Naysayers accused Lagrange of running a four-year-old French invader at Epsom and ordered veterinarians to inspect the filly’s teeth to assess her age.

“This victory, in a major national event, of a foreign filly, had the gift of unleashing the fury of the crowd, and the mare, as well as her jockey, owed it only to the protection of the police to be able to return to the weighing area,” wrote Lee.

Fille de l’Air—“or ‘Fiddler,’ as she was liable to be called (in imitation of ‘Parisian’ speech),” wrote Black—amassed 10 wins in 16 races as a three-year-old in 1864, including the Newmarket Oaks and Derby and the Moulins Saint-Léger. Adding to the confusion surrounding “Walking Lion” and its rightful race, the filly finished third in the 1864 edition of the Grand Prix de Paris behind first-place French runner Vermout and second-place Blair Athol, winner of that year’s Epsom Derby. Ironically, not only did Fille de l’Air suffer a loss in the Grand Prix de Paris that was mistakenly attributed to her, but she was also disqualified and had to forfeit her third-place purse money, her jockey not weighing in following her defeat due to a miscommunication that occurred at the scale. She returned at the Paris Autumn Meeting in the Grand Prix du Prince Impérial (Prix Royal-Oak) to beat Vermout, her only rival in this race and in the Continental St. Leger at Baden-Baden in Germany, where she triumphed again over the colt and also won the Prix de Lichtenthal.

The year of “Walking Lion” was Fille de l’Air’s final year in training. She ran undefeated in five races in April and May 1865—including the victory for the trophy in question—beginning with two wins at the Newmarket Craven meeting, followed four days later by the first of a string of races held on three consecutive Sundays during the Paris Spring meeting at Longchamp. The filly first won, by four lengths, the Prix de l’Impératrice (5,000 meters/3m1f) and finished out the meeting with a two-length victory in the Le 7e Prix Biennal at 2 miles.

We have finally arrived at the mysterious race for the coveted “Walking Lion.” The filly’s second victorious outing of the Longchamp meet on April 30, 1865, was the inaugural running of the 2-mile La Coupe, the rightful race that awarded Barye’s “very beautiful” silver lion with a value of 10,000 francs as well as 6,000 francs to the winner. This was another easy win for the valiant Fille de l’Air, who despite carrying 63.5 kilos—nearly 140 pounds, and 15.5 kilos/34 pounds more than Quaker, her only opponent—she won the race by two lengths. Twelve were entered but only the two horses ran, and the three-year-old Quaker did not prove to be a formidable rival for the filly, who captured the prize “by taking a walk,” reported the French Le Temps newspaper.

“Quaker led the race, having a three-length lead; but, at the last turn, Fille-de-l’Air joined him, overtook him and arrived first, at a canter.”

Barye was most likely commissioned to create “Walking Lion” for the inaugural running of La Coupe in 1865. That year, a new competition was opened to French artists to submit an art prize for consideration for the annual race going forward, and the award of an art trophy continued until 1994. Stablemate Gladiateur won the 1866 edition of this race, and the Prix La Coupe Stakes continues to be contested at ParisLongchamp as a Group 3 race for four-year-olds and up at the 10f distance; this year’s running will be held on Sunday, June 11.

Fille de l’Air returned to England to run at Royal Ascot, where she experienced her only loss of the year by finishing fifth in the Gold Cup. The next day she won the Alexandra Plate (Queen Alexandra Stakes) over 12 other horses to conclude her racing career. A champion at various distances and a true stayer in marathons such as the Alexandra Plate (then 2m6f) and the Prix de l’Impératrice over three miles, Fille de l’Air garnered 21 total victories in 32 races, with second and third placings in eight contests, amounting to more than 400,000 francs. The acclaimed filly was memorialized by the Group 3 Prix Fille de l’Air (10½f), inaugurated in 1902 at Maisons-Laffitte racecourse and now contested at Toulouse.

While Gladiateur has his ParisLongchamp statue, Fille de l’Air, the “Girl of the Air,” the heroine of 1864 and one of the fleetest Thoroughbreds of her time, has the majestic Barye sculpture in solid silver honoring her fortitude as the winner of the inaugural running of La Coupe on April 30, 1865. How appropriate that she was awarded this prize created by Barye, the master animalier called the “Michelangelo of the menagerie” by art critic Théophile Gautier. Barye’s painstaking study of animals at the zoo and anatomy laboratory of Paris’ Jardin des Plantes enabled the sculptor to produce this work of art befitting the courageous filly of Count de Lagrange’s stable, who proved that French-bred racers could compete and win at the highest level of the sport—just three decades after the French Jockey Club’s formation in 1833. As elegantly described by Ballu, “the famous Lion qui marche, so beautiful, so proud, so fearsome in his wild demeanor, a pure masterpiece.”

EXHIBITION INFORMATION

“Walking Lion” has been on view since January 2023 as part of a temporary exhibition at the Walters Art Museum’s Hackerman House building, located at 1 West Mount Vernon Place, Baltimore, Maryland. See the museum’s website for more information on this installation, as well as the sculpture’s online collection listing that now references the research findings from this story. A follow-up piece about our research, published by French racing magazine Jour de Galop, can be read here.

NOTES

*With regard to discrepancies in Barye’s birthdate, according to the National Gallery of Art, Barye was born in 1795, a date revised in the 1990s from 1796 as a result of Martin Sonnabend’s recalculation of the Revolutionary calendar.

Fille de l’Air’s race record was compiled from reports in the following: The Sporting Magazine, united with The Sportsman, Sporting Review & New Sporting Magazine (London, 1865); Le Temps newspaper; Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times; and the Robert Black and Henry Lee books. A full list of resources for this piece is available upon request.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.